(This essay has benefitted greatly from criticism and input from Thierry de Baillon, CV Harquail, Dominique Turcq, Steve Seager, Johnnie Moore, Kevin Barron, Dave Pollard, John Kellden and various discussions with other thoughtful friends).

.

‘Networks make organizational culture and politics explicit’ – Michael Schrage

.

As our networked world evolves, prescriptive models with comprehensive sets of rules are becoming less and less effective. In our dealing with complexity and uncertainty, we as leaders, managers, and consultants often face the temptation to fall back on a too-prescriptive linear logic of cause-and-effect. We don, often without reflecting, cognitive straitjackets.

Straitjackets are devices worn to restrain agitated or unpredictable people. Typically they are jackets with long arms that tie or buckle behind the person wearing one, such that their arms (and thus their ability to do most things) are restrained. As for semantics — these are the written-down contextual forces that lace our straitjackets up tight.

Today, our semantic straight-jackets are bound by the prescriptive linear logic of cause-and-effect that evolved from the later stages of the Industrial Revolution. We strive to know how to do things better, faster, cheaper, at greater scale.

The models created to codify “how to do things better, faster, cheaper” are almost exclusively derived from yesterday’s and today’s mainstream management ‘science’. These models have led us directly into the modern re-engineered, optimized and streamlined business processes that surround us in our daily lives today. Today’s business processes, competency models for all sorts of work, and leadership and management models are all focused on this kind of short-term performance-related behaviour.

They are so common and widespread that they are used almost without thinking. As a result, just like buzzwords that may present a solid idea, but are diluted through popular and not- rigorous use, many of today’s models have come to be relatively meaningless in our new context.

They compete with each other for the attention of potential users. And they have the unintended effect of creating and maintaining boundaries for action and interaction that present obstacles to adaptability, responsiveness and the co-creation of innovation in our new context. The phrase “think outside the box” for encouraging creativity adaptability exists for a good reason.

As a result, as we face growing complexity, ambiguity and uncertainty, we are firmly in the grip of a mental model that exhorts us to cut through the confusion and focus on what to do in order to ‘win’. I remember an excellent example pointed out by Dave Snowden a couple of years ago when KPMG (I think) was promising on billboards to ‘cut through complexity to the solution’. Dave, as a knowledgeable authority on navigating complexity, chortled with derision at this presumptuous advertising

Most models offer and promise enhanced organizational effectiveness — winning, in other words. They are typically a combination of ‘solutions’ and ‘transformation’ that sell prescriptive advice. They are marketed as solutions, but are mainly packaging of observable patterns operating in defined and established contexts that are presumed to be stable and/ or repeatable.

Often as not, they generate much light and heat in the name of implementing responsiveness and an ability to navigate the growing complexity, whilst doing relatively little or nothing to grow or support real, flexible and sustainable responsiveness.

However, make no mistake. We in the western world (and around the globe) have benefited greatly during the past century from the codification and modelling of efficiency, planning forward, budgeting and our understandings of human psychology in the context of homo economicus.

The methods and models of « how-to » dominate

We’ve been living through the late stages of an era dominated by assumptions about predictability, efficiency, reproducibility, control of quality and an ongoing quest to replace expensive and variable human labour with processes and automation that delivers those characteristics at massive scale.

As the quest for reliable success and continuous improvement has continued and grown, it has come to define our times. During this journey, we have witnessed (via a plethora of semantically defined models) the evolution of the concepts of management science take shape in tools that codify:

– the division of labour,

– functional and service specialization,

– continuous assessment and monitoring,

– the widespread adoption of metrics, and

– the definition of what desirable performance meant.

These tools take shape as semantically-defined scales, grids and matrices that describe a model and how to use it. For a given challenge they spell out in “how-to” format various levels of generic responsibility, required skills, and the competencies leading to high performance. Over the past two decades, attempts have begun to appear aimed at opening up the constraints these core assumptions imposed (for example, the Balanced Scorecard, Agile and Lean management methodologies, etc.).

However, there is often considerable friction, as the world of conventional management remains saturated with many methods and models for ‘how- to’:

– enhance efficiency

– harness human potential

– organize most effectively for repeatable successful delivery.

The limits of these assumptions are appearing as networked flows of information bring constant churn and increased complexity. Significant re-conception is necessary with regard to what to think about, how to think about it and how to guide responsive action.

All models, all the way down

Today it seems such modelling is what we know how to understand. Building and implementing models is how we tackle issues, problems and opportunities. And relatively rapidly they become used as prescriptive solutions. Unfortunately they are less and less adequate for increasingly complex conditions. Executives and managers want to know ‘what will work’ — without having to do the hard work of thinking critically through issues of human dynamics involved in cognition, learning, clear communications and resolving issues identified through ongoing feedback.

After 75+ years of management science we have created our own straight jackets. They are us and we are them. We semantically defined the forces that have now become obstacles to flexibility, responsiveness and innovation. Our prescriptions are as follows:

– Models for Agile and Lean methodologies that ‘work’, as opposed to their use for guidance

– The ‘one true’ organizational design model for successful performance

– Fixed competency models, job descriptions, developmental learning and management models

– The ‘perfect’ CV and resume

– ‘Recipes’ for change management and digital / organizational transformation

Sustained responsive adaptability and true effectiveness in conditions of growing complexity seem elusive. At best, there is improvement in how things are carried out, get done and are delivered, but almost always only for a relatively short period of time. Then, things change once again. True adaptability and responsiveness remain elusive. So what’s going on?

Complexity without comprehension

The above reminds me of the oft-cited debate between the applicability and utility of Best Practices models versus Good Practices; in effect, rather than applying best practices as prescriptive, using good practices involves exploring models and using more fundamental principles to actually think through what to do, why and how.

Prior to the widespread mania for implementing massive, comprehensive and enterprise- wide ERP systems (aimed at standardization and focused on efficiency), during the 80’s we had begun hearing more and more about learning organizations, organizations as living human systems, and success stories with respect to experimentation in self-directed work groups and self-management. However, virtually all of this burgeoning experimentation was effectively crushed by a widespread onslaught of the ERP-isation of the enterprise.

More recently there has been rapidly growing interest in concepts such as the supposedly self-management-oriented Holacracy, the emerging concepts of the “Responsive Organization” (Microsoft) and Holonomics’ “Squads, Tribes, Guilds and Agile Organizations”. These new models give a nod to self-direction and self-management in human-centered frameworks, but seek to create a model that can be implemented as a set of rules that will apply to a new set of conditions (hyperlinked and networked flows of information and feedback).

However, as these new conditions have begun to have impact on more of our activities within an organizational context, it’s no surprise that the primary examples of effectiveness and adaptability cited today refer most often to the enterprises recognized 20 or 25 years ago as robust examples of self-directed learning organizations (W.L. Gore & Associates, Semco, Mondragon and a handful of others).

The organizational world is getting more complex, rapidly. As the complexity grows, so has the desire for simple and easily-implemented solutions. This polarity is understandable. But, humans are messy and and have individual cognitive, psychological and emotive profiles and capabilities. In effect, each person has their own configuration of cognition, psychology and motivation that affects their reasons for being and doing. They do not yield easily to standardization models. It is my belief that most people have reacted to the onslaught of competency models (for example) as one would react to being asked to try on a straitjacket … livable but constraining and uncomfortable.

Understanding and using complexity

Hyperlinked networks that have connected us and allowed us to speak out and speak up, work out loud, etc. are making explicit the human diversity of perspective and the attendant messiness, and have amplified the problem that management science models set out to conquer.

Our continuing reliance on those prescriptive semantically-defined models of “how to” do something, “how to” get it right next time are holding us back. I do not believe there will be any more correct or “right” models upon which leaders and decision-makers can rely to generate effectiveness.

Perhaps rather than using models to try to control and predict what networked humans will do in the quest to generate flexibility, responsiveness and ‘performance’ we should seek to shape and guide those activities through understanding diversity and uniqueness and learning to operate in conditions that more and more often are becoming complex.

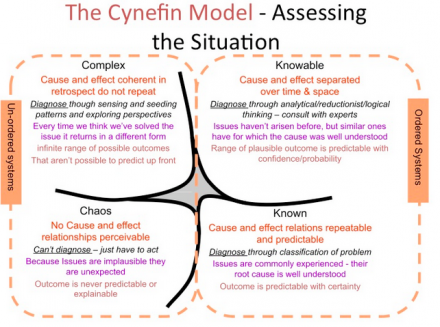

Dave Snowden and collaborators developed the Cynefin Framework about a decade ago. It’s purpose is to help executives and managers navigate complex conditions more effectively.

the Cynefin framework, which allows executives to see things from new viewpoints, assimilate complex concepts, and address real-world problems and opportunities. (Cynefin, pronounced ku-nev-in, is a Welsh word that signifies the multiple factors in our environment and our experience that influence us in ways we can never understand.) Using this approach, leaders learn to define the framework with examples from their own organization’s history and scenarios of its possible future. This enhances communication and helps executives rapidly understand the context in which they are operating.

…

The framework sorts the issues facing leaders into five contexts defined by the nature of the relationship between cause and effect. Four of these—simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic—require leaders to diagnose situations and to act in contextually appropriate ways. The fifth—disorder—applies when it is unclear which of the other four contexts is predominant.

“A Leader’s Framework for Decision-Making“, Harvard Business Review – November 2007

The Cynefin framework (below) and the use of sense-making capabilities as engendered in the Sensemaker suite of software are essential in helping us move beyond the semantic straitjackets embodied in cause-and-effect models of “how to” do things.

The Cynefin model presents us with a different narrative, both semantic and syntactic, of the nature of work in the age of ever-changing conditions and ever-flowing information. By becoming regular users of such a framework, we will better understand what kinds of activities and work confront us, and thus what kinds of change- work needs to be considered.

From a semantic point of view, the indicators set out in the Cynefin framework are descriptions of core conditions and possible action. Instead of cutting through – and often dismissing – complexity, these indicators are not prescriptive but rather support enquiry, critical thinking and analysis about what paths of questioning. Critical thinking and action(s) are likely to offer effective responses to complexity that will not yield to prescriptive standardized responses.

Here is a simplistic interpretation of the different Cynefin domains:

Known – work/activity that is well established and necessary, unlikely to change much and thus a candidate for become automation and / or robotization,

Knowable – work/activity that structured yet requires ongoing refinement wherein analytics, intelligent pattern-seeking and algorithmization in defined areas will yield improvement(s),

Complex – work/activity where seeking and observing patterns and deciding what kinds of constraints are likely to clarify patterns results in possibilities for stabilization and then ongoing refinement,

Chaos – probing with action, stimuli and experimental constraints to seek the emergence of patterns, and

Disordered – work that has no focus or purpose or that doesn’t make any sense in the current context (my interpretation re: work activities)

Furthermore, the model doesn’t provide a linear, predictable path from a domain to another. It gives neither prescriptive response nor sequential approach to how things should get done. Its open syntax favours experimentation, oblique thinking, and holistic understanding of the different patterns at stake.

Semantic frameworks are for guidance, not control

To untie the straitjackets that are constraining our capacities to successfully adapt to present and future business conditions, we need to become able to discern between the different domains outlined in the Cynefin model, to consider different approaches to complexity than to complication, to the unknown than to what we know.

Frameworks such as Cynefin provide us with guidance towards new more effective ways of describing exploration and actions, while their open syntax allow us to stay away from the prescriptions that worked in a predictable environment in order to prototype and apply novel approaches to organizational effectiveness.

Certainly this is not an easy task. But as prescriptive models with a comprehensive set of rules are likely to become less and less effective as our networked world evolves, we cannot hide our fear of complexity behind them anymore.

To tame this fear, and grow our individual or collective potential, we need first to learn the building blocks of a new semantics, then to play with them according to a new syntax. Learn and play, not prescriptive methodologies, are the fabric of organizational improvement.

[…] Understanding Semantic Straitjackets: How today’s management science stifles creativity, innovatio… […]

[…] Husband writes about Semantic Straitjackets a useful way to describe the many models and processes used in organisations to help manage […]

Excellent. I wonder how job titles and org charts work in this world?

“” I wonder how job titles and org charts work in this world “”

An excellent question, and one where some initial responses are beginning to appear. There are ‘experiments’ underway in a number of places in the world of which I am aware, where people are seeking and beginning to work with and understand what is beyond job titles and org charts.

Please feel free to contact me via email if you want to discuss further.

[…] http://wirearchy.com/2015/10/12/understanding-semantic-straitjackets-how-todays-management-science-s… […]